Palm Sunday celebrates the day Jesus entered Jerusalem in a remarkable procession that sealed his death warrant.

Historians don’t agree on the exact year of this extraordinary event. According to the gospel of John, it was a year in which Passover Eve fell on a Friday.

Most scholars would put this in either the year AD 33 or AD 30. I think the evidence leans a little toward AD 33, but it wouldn’t shock me if it was AD 30 instead.

On that fateful Sunday, Jesus left Jericho in the morning and made the 16-mile climb up the Jericho Road to Jerusalem.

He had plenty of company. His twelve disciples and numerous other followers surrounded him. Very likely his mother and his brothers and their families came along also. Hundreds of pilgrims from Galilee and the Jordan Valley walked on the same road that same day.

The Jericho Road rises in elevation by about 3000 feet. It passes through arid country, so the travelers carried plenty of water. This road was notorious for bandits, so most of the men also carried short knives for protection.

Excitement hung electric in the air.

Passover and the City of the Great King

It was the week before Passover, and many thousands of Jews were headed into Jerusalem, the City of the Great King.

No doubt, they were singing psalms. No doubt they were retelling the story of the first Passover, when God miraculously released their ancestors from slavery in Egypt. No doubt they were wondering if this year, God would raise up a new deliverer like Moses to rescue them from the oppression of Rome.

For some centuries, the prophets had given oracles about this deliverer, a man who would be the anointed King of Israel, the son of David who would restore the kingdom of David and sit again on David’s throne.

In Hebrew they called this coming king “Mashiach,” a word which just means “the anointed one.” When you transliterate this word to Greek and then transliterate it again to English, you get the word “Messiah.”

In first-century Judea, Passover seemed the best time of year for Mashiach to appear.

On the Mount of Olives

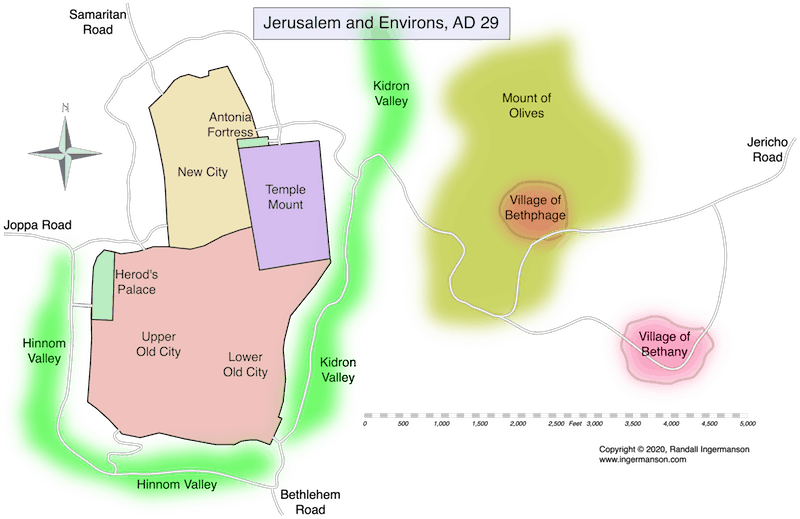

The road from Jericho to Jerusalem peaked at the Mount of Olives. There were two villages here, Bethany and Bethphage. Here’s a map I drew for my novel Son of Mary that shows these villages and Jerusalem:

When Jesus and his entourage reached the Mount of Olives, he sent a couple of his disciples ahead to one of these two villages to borrow a donkey. (It’s not clear which village he sent them to, but my own best guess is Bethany, where he had friends who wouldn’t mind loaning him a donkey.)

We don’t know which two disciples he sent, but I’d guess Peter and John got the job. These were two of the three main disciples of Jesus, and the stories from this time seem to show Peter and John as close friends.

When they returned, Jesus took a seat on the donkey.

At which point, he committed sedition against Rome.

Mashiach’s Donkey

Among the ancient oracles from the prophets was one in Zechariah 9:9 that spoke of a future king of Israel who would come to Jerusalem riding on a donkey. He would go on to rule all the earth, commanding all the nations.

Jesus and his disciples and every single person on the road knew this oracle. The term “Mashiach’s Donkey” is a phrase that still lives today in Jewish lore.

When Jesus sat on Mashiach’s Donkey, he was making a powerful political statement. He was making a claim to be the king of Israel.

And the crowd went wild.

They began singing one of the victory songs that are traditional at Passover—Psalm 118. We know this, because the gospels record some of what they said in Mark 11:8-10 and it comes straight from Psalm 118:25-26.

The English word “hosanna” is just a transliteration of the Hebrew “hoshia na” which means “save us now!”

And every Jew of the first century knew what it meant for God to save them. It meant that God would go to war on their behalf. He would smite their enemies, as he smote the Egyptians in the time of Moses. As he smote the Canaanites in the time of Joshua. As he smote the Philistines in the time of David.

Entering the City of the Great King

The Mount of Olives is quite steep, and the road slants at an angle to make the slope easier. I have walked this road several times, and it’s challenging.

When Jesus and the crowd reached the bottom, they were in a narrow valley (the Kidron Valley) between Jerusalem and the Mount of Olives. They were looking straight up at the Temple Mount, but there was no gate directly into the Temple Mount from where they stood.

At this point, they had a choice.

They could go northwest around the corner of the Temple Mount to the north gate. This was a short walk of a few hundred yards up a moderate slope.

Or they could turn south and walk half a mile down the steep Kidron Valley to the gate at the southwest corner of the city. If they chose this path, they would then enter Jerusalem and walk another half mile right back up the steep hill which they had just walked down.

The southern route was at least five times farther than the northern one. It was steeper. It took a lot more physical effort. Jesus and the crowd had already walked sixteen miles up a long, dry desert road, and they were tired.

By all logic, Jesus and the crowd should have taken the easy northern route into Jerusalem.

Tradition says that Jesus and the crowd went south.

Why Jesus Took The Long Way Around

Why did Jesus take the longer, harder way when everyone was already tired from an arduous day’s walk?

Because the short and easy northern route entered the Temple Mount through a gate right next to the Antonia Fortress, manned by Roman soldiers. These soldiers had only one job—to prevent an armed insurrection.

Most of the men in the crowd with Jesus probably carried a short knife for personal protection. If you went traveling through bandit country without a weapon, you were just dumb, and these were experienced travelers. They weren’t dumb.

The Romans would have seen them as armed and dangerous. And they were right. This crowd—the entire crowd—was committing sedition by their words. And they were primed to take it to the next level. To violent insurrection.

If the Romans had seen them, they’d have come out in force. They wore armor and carried better weapons, and they were trained to fight as a team. It would have been a slaughter.

My view is that Jesus didn’t have a military bone in his body. His idea of Mashiach was not a military-leader king. His idea of Mashiach was a humble servant-king.

But he knew perfectly well that not one person in the crowd shared his ideas. The crowd surrounding him wanted blood. Roman blood. (Forty years later, their sons and grandsons got exactly that, in the terrible Jewish Revolt of AD 66-70. They began it with a slaughter of Roman soldiers.)

Jesus knew exactly what would happen if this crowd mixed it up with the Roman garrison at the Antonia Fortress.

So he took the southern route, and the soldiers in the Antonia Fortress never saw the commotion.

The Death Warrant of Jesus

By taking the safer route, Jesus saved the lives of many hundreds of his fellow Jews. Even so, he signed his own death warrant.

We’ll see exactly how that worked out over the next few days of Passion Week in the next blog post.

Stay tuned…

[…] my last blog post, Jesus and Palm Sunday, I talked about how Jesus committed sedition by climbing on a donkey and riding down the Mount of […]

[…] Jesus made a triumphal entry into Jerusalem riding on a donkey. See my recent blog posts on this, Jesus and Palm Sunday and Jesus of Nazareth, King of the […]

[…] But we know there was no massacre, so probably Jesus went south along the Kidron Valley to the gate at the southeast corner of the city. For more on that, see my blog post, Jesus and Palm Sunday. […]